Lest we forget. This war shaped all our lives, even of those not born till afterward. For thus of who were young adults 40 years ago, the draft, the enormous expense of the destruction (bombs, aircraft, medical attention to the wounded, junkets of congressmen), the deep political divisions (antiwar vs. LBJ and McNamara 'Realpolitik'), the clashes of protesters and police, the career decisions and other moral dilemmas, the grieving for the enormous human losses skewed the lives of all of us — and that was just in the United States. The consequences in Vietnam were enormous, too enormous for most Americans to even think about at any length or depth — because thinking about it, seriously, could bring us to the brink of despair, or of action.

Vietnam, the ongoing memory | Harvard Gazette

We destroy the beauty of the countryside because the un-appropriated splendors of nature have no economic value. We are capable of shutting off the sun and the stars because they do not pay a dividend. — John Maynard Keynes

2014/12/25

2014/12/18

The Paris Commune, and them and us

Fighting Over the Paris Commune | The New Yorker

Right

on my subject. All the contradictions that Adam Gopnik mentions are

themes of my novel in progress. I'd quibble with some of his

characterizations — Raoul Rigault and others were no angels, communeux or communards

(they themselves generally used the first term) were far less inclined

to annihilate their enemies than were the Versaillais commanders,

“well-dressed ladies” really did do some of those horrible things after

the massacre (we have ample newspaper accounts, by foreign and

presumably objective reporters). And and then there's this remark,

Yes,

there were such instances, not only but mostly by "communards" — the

most vivid testimony is in Vuillaume's "Red Notebooks"(also the best

source on the crazed self-importance of Vuillaume's one-time friend

Rigault). But in the last days and hours, the desperation of the

Commune's defenders led to uncontrollable, mad rage on the last

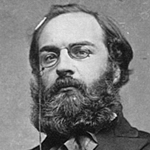

remaining, eastern streets of Paris. Eugène Varlin, draped in his

official Commune sash, tried mightily but failed to save a group of

hostages on the rue Haxo (image right).

Yes,

there were such instances, not only but mostly by "communards" — the

most vivid testimony is in Vuillaume's "Red Notebooks"(also the best

source on the crazed self-importance of Vuillaume's one-time friend

Rigault). But in the last days and hours, the desperation of the

Commune's defenders led to uncontrollable, mad rage on the last

remaining, eastern streets of Paris. Eugène Varlin, draped in his

official Commune sash, tried mightily but failed to save a group of

hostages on the rue Haxo (image right).

A bloody mess, and it's true that the "Communards" were hardly united, except in their anticlericalism, and had they "won" or at least held out for a longer time, it's not at all clear that the progressive, democratic and humanitarian leaders among them would have ruled. Well, all this is rich material for my novel "The Bookbinder" (working title), which will be not only about the Paris Commune of 1871 but about us and our world today.

|

| Raoul Rigault |

There are many instances in Merriman’s account of people being saved by accident or by the act of a charitable and decent individual. But there is scarcely an incident of a principled humanity, where one side or the other refused to massacre captured civilian prisoners or hostages on the ground that it was the wrong thing to do, rather than impolitic at that moment.

Yes,

there were such instances, not only but mostly by "communards" — the

most vivid testimony is in Vuillaume's "Red Notebooks"(also the best

source on the crazed self-importance of Vuillaume's one-time friend

Rigault). But in the last days and hours, the desperation of the

Commune's defenders led to uncontrollable, mad rage on the last

remaining, eastern streets of Paris. Eugène Varlin, draped in his

official Commune sash, tried mightily but failed to save a group of

hostages on the rue Haxo (image right).

Yes,

there were such instances, not only but mostly by "communards" — the

most vivid testimony is in Vuillaume's "Red Notebooks"(also the best

source on the crazed self-importance of Vuillaume's one-time friend

Rigault). But in the last days and hours, the desperation of the

Commune's defenders led to uncontrollable, mad rage on the last

remaining, eastern streets of Paris. Eugène Varlin, draped in his

official Commune sash, tried mightily but failed to save a group of

hostages on the rue Haxo (image right). A bloody mess, and it's true that the "Communards" were hardly united, except in their anticlericalism, and had they "won" or at least held out for a longer time, it's not at all clear that the progressive, democratic and humanitarian leaders among them would have ruled. Well, all this is rich material for my novel "The Bookbinder" (working title), which will be not only about the Paris Commune of 1871 but about us and our world today.

2014/11/20

2014/10/22

An earthquake of a book about an earthquake event

Ten Days that Shook the World by John Reed

Ten Days that Shook the World by John ReedMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

This vivid first-hand reportage of the first ten days of Bolshevik power, from the seizure of the Winter Palace in Petrograd, 25 October 1917 (by the Julian or Old Style calendar, which corresponds to 7 November 1917 in the Gregorian or New Style calendar) to its consolidation in Moscow and gathering force in the rest of Russia, is strongly partisan, pro-Lenin and the Bolsheviks, but also scrupulously documented and honestly, frankly observed. Reed describes the appearance, voices and quirks of the protagonists, including anonymous soldiers, sailors, Red Guards and workers, making apparent the chaotic, improvised character of most of the events, and the quick-witted decision-making and sometimes pitiless actions, especially those of the austere and uncompromising Lenin and the far more colorful, dramatic, and sarcastic Trotsky that repeatedly saved the Bolshevik insurrection from impending disaster. Reed does not hesitate to describe flaws, doubts and internal disputes, showing how precarious was their adventure and how close to failure. He collected leaflets, newspapers and bulletins from all parties, many of them reproduced in the book, and learned enough Russian not only to translate these but also to conduct interviews of Kerensky, Trotsky, Lenin and many other actors in this drama. Events in Petrograd and, later, Moscow are acutely observed, making this an indispensable account of the violent, chaotic, suspenseful first days of the seizure of power by masses of workers and soldiers with no administrative experience and, for all but the few intellectual leaders of the various parties, scant literacy or general knowledge of culture or history.

Those first ten days did indeed shake the world: they determined Russia's withdrawal from the Great European War, shaking diplomacy and strategy for all the other powers involved (Germany, Austria, England, France, the US especially), and created the beginnings of the hastily assembled Red Army which would eventually to triumph over the many fronts in the civil war in the world's largest nation, which was also one of Europe's least developed. The book itself continues to shake readers loose from more simplistic interpretations of this terribly complex series of events that redrew the lines of world power for the rest of the 20th century.

This 1922 edition is the first to appear with a foreword by Vladimir Lenin, encouraging all to read it. Reed was surprised and delighted to learn that Lenin had actually read it, and apparently was not offended by the very frank reporting that did not glorify the Bolsheviks, even though it supported them. Recognized even by the fiercest opponents of Communism as splendid and indispensable reportage, reader demand has not diminished and the book continues to be reissued by any number of publishers and in virtually all languages. Even if you have no particular interest in the Russian revolution (unlikely, but who knows?), you will find this book a model of vivid, scrupulous journalism — as Reed had already demonstrated in an earlier book, "Insurgent Mexico" but was unable to repeat after "10 Days," because he died in 1920 of typhus, in Russia. He was 33. He is buried alongside other revolutionary heroes just outside Lenin's mausoleum in Red Square.

View all my reviews

2014/10/07

Anti-boycott petition

This just come to my in-box from a scholar at Tel Aviv University. I agree (broadly) with the argument that an academic boycott is not the way to encourage dialogue, and dialogue is what we most need in the age of extremisms. Boycotts of many products may be effective, for example, a boycott of the Israeli weapons industry might be a very good thing — and might even make the Israel government respond. But boycotts of academic or any other intellectual interchange — "I refuse even to listen to you" sort of boycotts — will not only be utterly ineffective to change Israeli (or anybody's) policy, but will simply hamper much needed communication.

They are seeking signature from academics, but I am not affiliated to any academic institution, so rather than sign I'm expressing my support here. Follow the link to read the petition, though I think Professor Dreyfus' presentation of the case is especially clear.

Friends,

May I suggest that you consider signing this petition against academic boycotts, specifically academic boycotts of Israel’s academic institutions, scholars and students. The petition originated in the USA but is intended to be signed by scholars in all

countries.Personally, I oppose much of our present government’s policies with respect to Palestinians and a Palestinian state. So do many of my colleagues. However, I oppose an academic boycott in principle (see Zvi Ziegler’s arguments below) and in practice: A boycott is likely to weaken voices against government policy and strengthen the right wing in Israel.

Tommy DreyfusBest wishes,Tommy

Zvi Ziegler is head of the committee gathering signatures. He writes,

Our approach is that academic boycotts are harmful to the progress of mankind , and that science should be pursued without discriminating against people on account of their race, gender, nationality, politics, etc. This approach is identical to the one expressed by several national academies of science, including the USA one.

2014/10/01

Brilliant images hold up a wispy tale

Light Years by James Salter

Light Years by James SalterMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Salter is famous for his beautiful sentences, beginning here with “We dash the black river, its flats smooth as stone. Not a ship, not a dinghy, not one cry of white. The water lies broken, cracked from the wind. This great estuary is wide, endless.”

The opening of Light Years seems to open a world, a very particular world of rough, unyielding nature — river, trees, rocks — and the precarious and unstable marks left by generations of humans, down to the youngest, two little girls who crouch outside the bathroom, urging their story-telling papa (who is soaking in the tub) to come out and tell them more about their pony that, according to him swims to the bottom of the river to eat the onions that grow there.

The little girls grow up, their story-telling father continues telling fables but mostly to himself, while their mother keeps trying out new ways, and new lovers, in a mostly unsuccessful effort to keep herself interested in life. Their pets, including that errant pony, a tailless dog and a turtle, grow old and all but the turtle die, as do some of this family's friends — lots of little events, and some bigger ones, occur over the 15-some "light years," 1958 to about 1973, through which we observe a man and a woman, the parents of those little girls, from their home in rural New York to their work and play in New York City, and then briefly (and separately) to Italy and Switzerland, before each — separately still — returns to the soggy land around that black river, its familiar buildings decayed and newer, unwelcoming ones thrown up as gaudy future ruins.

And that’s about it for the story. No one here is driven by any great, unforgiving ambition, but the man and woman and all their friends move mostly by inertia, nudged along at times by dreams and impulses, which are mostly disappointing when fulfilled. Still, the book is so beautifully written, the people are so believably individual, and the weather and texture and look of the sites so vivid, that it is a joy to read. The opening lines, about the river and the sea birds and its “dream of the past” are as entrancing as the opening lines of García Márquez’ One Hundred Years of Solitude, but with this difference: the first lines of the latter book — the Colonel facing a firing squad and remembering his childhood — contain the hint of the whole complicated story. In Light Years, there almost is no story beyond the images of different moments in the slow and uncomprehending maturing, or simply aging, of a man and woman as they drift apart and with no common project.

View all my reviews

2014/09/18

From the center of the maelstrom of the Paris Commune

Mes cahiers rouges: souvenirs de la commune by Maxime Vuillaume

Mes cahiers rouges: souvenirs de la commune by Maxime VuillaumeMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Maxime Vuillaume’s “red notebooks” (cahiers rouges) contain some of the most vivid first hand testimony of all the writings on the Paris Commune. Vuillaume knew almost all the major players, some of them very well, and was himself an important actor, as a founder and editor of one of the most popular newspapers of the Commune, Le Père Duchêne.

Only 26 when he barely escaped execution in the bloody final week of the Commune (May 20-28, 1871), Vuillaume wrote the first post-commune reports in clandestine documents from his exile in Switzerland, before the amnesty (1880) permitted him to return to France. For years, he was reluctant to publish his notes, for fear of injuring people still living or being sued by their descendants. But finally, some 30 years after the annihilation of the commune, a younger journalist, Lucien Descaves, persuaded him to put them into shape and publish them, and Vuillaume then also began to compose and publish additional "cahiers", sometimes correcting things in the earlier ones or adding detail, and sometimes taking on aspects of the Commune that he had not personally experienced but researched through documents and interviews. All of these, the earliest and most personal and the later researched reports, have been gathered together in this edition of the “red notebooks.”

Vuillaume's Père Duchêne was a foul-mouthed, rabble-rousing, over-the-top scandal sheet, in imitation of the original Père Duchesne of Jacques-René Hébert that rallied the sans-culottes from 1790 until Hébert was guillotined in 1794. As in the original version, the "Old Man" or "Père" of the title was the fictional voice of a man of the "people", i.e., the unprivileged, lambasting the rich, the clergy, and anybody else seen as an oppressor. Its readers probably knew the paper was not to be trusted — reporting events that may or may not have occurred — but they bought it anyway, so many of them that the paper made more money than expected. They must have delighted in the invective against the “jeanfoutres” and “bougres” (gross insults, common in speech but rarely seen in print in those days), meaning all those opposed to the Commune, including Catholic clergy, local bourgeois and the government in Versailles.

The more mature Vuillaume, traumatized by the horrific bloodshed and prolonged repression of the end of the commune, became a much more serious, careful and responsible reporter, but without losing his capacity for vivid and impassioned description. Thus all these reports or “notebooks” are well worth reading, even those that go over material also covered by his journalist contemporaries Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray and Jules Vallès (both of whom Vuillaume knew well). But by far the liveliest cahiers are those on the experiences closest to him: Cahier I, “Une journée à la cour martiale de Luxembourg,” describes the army's systematic killing of suspected communards after their final defeat and Vuillaume’s own very narrow escape from execution; III, “Quand nous faisions Le Père Duchêne,” about all that he and his equally young partners, Eugène Vermersch and Alphonse Humbert, had to go through to get the capital together, write and distribute a daily paper in that period of intense debate, street agitation and combats, and IV, “Quelques-uns de la Commune”, intimate portraits of communards including Raoul Rigault, who in his last days was the commune’s chief prosecutor. Samples from some of those sharp-tongued articles are included in this book, but for the most part, the mature Vuillaume writes a more temperate prose, but still with passion for the lost cause of the Commune.

See also my reviews of Jules Vallès' fictionalized account, L'Insurgé, and Lissagaray's Histoire de la Commune de 1871

View all my reviews

2014/09/08

Memory Booster | HMS

Another step forward in understanding how short-term memory works! And without it, we couldn't create long-term memories — or so I suppose, and that's what most specialists also believe. We may all be wrong, but now that they've identified this calcium sensor in short-term memory, they may be able to test that hypothesis.

Memory Booster | HMS

Memory is all we have to work with, we authors. So this really matters. For more reflections on this topic (e.g., my note on Elkhonon Goldberg's book, The Wisdom Paradox) click on "memory" keyword below.

Memory Booster | HMS

Memory is all we have to work with, we authors. So this really matters. For more reflections on this topic (e.g., my note on Elkhonon Goldberg's book, The Wisdom Paradox) click on "memory" keyword below.

2014/09/05

Visit to Russia — Susana's travelogue

Here is my accomplice Susana Torre's account of our recent trip to Moscow and Saint Petersburg. For more writing and other work by Susana, see her website, Susana Torre.

SUSANA AND GEOFF’S TRIP TO MOSCOW AND SAINT PETERSBURG, JULY-AUGUST 2014

SHHHHHHH!!! The young guards were, very loudly, making sure we didn’t make any noise going down the steps of Lenin’s Mausoleum in almost complete darkness. It’s impossible to tell if the figure lying in state with face and hands precisely lit is the real mummy, or a wax representation. All the same, we wanted to say goodbye in our last day in Moscow to the symbol of the momentous social changes brought about by the October 1917 revolution. Goodbye, Vladimir Ilych. Goodbye, John Reed and Alexei Shchusev buried with many others along the Kremlin wall.

We made this trip intending to make the picture in our heads, formed by our readings by historians, theoreticians, protagonists and inspirers of the revolution, more nuanced and complete. Not exactly a nostalgic trip for lost ideals, but to see first hand whatever remained of the material evidence of those ideals, and to see what had become of them today in Moscow and Saint Petersburg (called “Peter” by the Russians). First Moscow, and then a trip on the fast “Sapsan” — “Hawk” — train to “Peter”, through flat farmland, villages and densely packed residential high-rise suburbs. Geoff had resumed his college Russian language studies, and managed to communicate and read all the Cyrillic signs, indispensable to travel by public transportation – especially the subway, as efficient, clean, advertisement-free, frequent and fast as touted in the tourist guides, including the lavish use of marble surfaces and alabaster fixtures.

On our first day in Moscow we visited Krasnaya Ploshchad, Red, or Beautiful, Square (“krasnaya” has both meanings in Russian), the vast open space, formerly a market, just outside the walls of the Kremlin. The brightly colored multiple onion-domes of St. Basil’s Cathedral dominate one end, and the more somber, red-brick State Historical Museum the other, over 2,000 feet away. Stretching along part of the wall is Lenin’s classical-cum-constructivist mausoleum, and facing it across the square, 230 feet away, sits the huge GUM, the largest covered arcade in the world. Built in 1890 to impress Europeans and create an enclosed place for the nobility to consume the latest Parisian fashions, today it is a private shopping mall known to locals as “the exhibition hall of prices”. From the restaurant terrace in front of GUM, we watched the people ambling across the great space, at a much more leisurely pace than the purposeful walk of people in Western capital cities. Maybe this is because the square is a destination unto itself, not a passing-through place. It is from here that the avenues structuring the city radiate, intersected by multi-lane, high-speed ring roads that pedestrians may cross only by underground passages. To my surprise, the interior of St. Basil’s Cathedral (a Museum since 1929) was not a large nave, but a collection of eight chapels around a ninth, central one less than 700 square feet in area. We had to search through the narrow connecting corridors to find one with especially great acoustics, resonating with the voices of a four-man vocal group.

Even the Cathedrals within the Kremlin walls followed a similar pattern, churches meant for a privileged few and with no ambition to include the unwashed masses. We were more impressed with the model of Catherine the Great’s insanely ambitious Grand Kremlin Palace, now in the Architecture Museum than with the existing Kremlin itself. Had it been built, monumental Neo-Classical double colonnades would have surmounted the entire Kremlin Wall facing Red Square.

Everywhere we saw the signs of historical continuity between Tsarist, Soviet, and post-Perestroika Russia: cathedrals turned into museums; streets in Moscow’s center lined with mansions of the aristocracy now put to public uses or turned into homes for the “oligarchs”, including the Art Nouveau gem of a house the last Tsar had built for a lover — now a museum — with the balcony from which Lenin harangued the partisans after he had taken over the house for Bolshevik

headquarters. One discontinuity, Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, demolished by Stalin to make room for a Palace of the Soviets that was never built, was rebuilt in the 1990s. Here, Pussy Riot staged the 4-minute concert that landed two of their members in jail for almost two years. The cathedral faces the river and a pedestrian bridge that brings Moscow’s youth into the fashionable Strelka café, and the nearby, exceedingly ugly 15-story high statue by the apparatchik architect/sculptor Zurab Tsereteli. The sculpture was a gift representing Columbus, intended for the US but rejected, and here displayed with a new head, that of Peter the Great. (Patrick Murfin blog, photographer uncredited)

Another continuity is the ubiquitous orange and black striped ribbon of St. George, symbolizing fire and gunpowder, that is everywhere attached to car handles and rear-view mirrors, to Putin’s lapel and the lapels of bodyguards in black suits in 90-degree weather. The ribbon is a component of military decorations awarded by imperial, Soviet and current Russia governments, now used to show support for pro-Russians in the disputed regions of Ukraine. Many coffee mugs in the souvenir section of the gigantic Izmailovo flea market had the map of Crimea next to the legend: “It’s OURS!” The popular mood seems to be with Putin, and the Russian TV channel in English kept reporting on the lies of the Western media about Russia’s military involvement in the Donbass.

Among the dozens of house museums where artists and writers lived, the one I wanted to see most was that of Anatoly Lunacharsky, Lenin’s Commissar of Enlightenment, a great intellectual and promoter of the artistic avant-garde; he staged a happening avant la lettre, a trial against God for crimes against humanity, in which the deity was condemned to death and “executed” by a firing squad shooting machine guns into the sky. When we could gолигарх, i.e., “oligarch”.

et no answer on the phone for an appointment, we simply showed up at the address and rang the bell. A burly man— evidently the caretaker — came down to inform us, by gesture and the few words we could understand, that the apartment was now privately occupied; with a semi-apologetic grin, he explained in one word:

In both Moscow and St. Petersburg we visited art and political history museums. In Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery annex, we were able to see the 50% of George Costakis’ extraordinary art collection that he was obliged to leave behind when he moved to Greece, including Malevich’s Black Square and some of the best pieces of Natalia Goncharova, which establish her role as the inspiring founder of new movements. It was enlightening to see them for the first time in the context of earlier and later works by Russian artists not well known in the West. The focus of the contemporary art world is Moscow’s “Garage”, a would-be museum currently housed in a temporary, unremarkable structure designed by Shigeru Ban, awaiting its permanent location in a Soviet era pavilion being remodeled by Rem Koolhas, in a clear effort to become an international destination. Although we are not entirely up-to-date with Russian contemporary art, we had liked the rambunctious energy of songspiel videos by the art collective Chto Delat? (What is to be done?) http://vimeo.com/12130035 -- but the exhibition at Garage, with work by artists in the periphery of the Russian Federation about the dislocation produced by the end of the Soviet Union, seemed trite and superficial.

Construction in Moscow’s center, especially in its main radial avenue, Tverskaya Ulitsa, seems to have stopped after Stalin built the Seven Sisters skyscrapers in the late 1940s and early 50s. The foundations for an eighth “Sister” bordering Red Square were used after Stalin’s death for the modern, monstrously big Rossiya Hotel (21-storeys, 3,200 rooms, police station, etc.), the biggest in Europe, which was finally demolished in 2006. It has become a contested site, with public pressure to use it for a park instead of a new entertainment center designed by Norman Foster. But a new International Business Center, boasting Europe’s tallest building, is nearly finished on a site beyond the third ring road. We saw its gleaming towers at a distance during our tour of Constructivist buildings – the workers’ clubs, communal housing and other emblematic projects built during the 1920s that embody the revolutionary social change made into architecture during the Bolshevik government’s first years.

We continued our search for places and buildings of that fateful period when we arrived in picture book Neo-Classical “Peter”. Such buildings can be found mostly in Narvskaya Zastava, the center of the workers’ movement during the events of 1917, still a proletarian neighborhood full of factories and streets with names like “Tractor” or “Barricade”. Two impressive relics are the Kirovsky District Soviet building, municipal offices still used for the original purpose, and the former humongous industrial kitchen supplying hot lunches to factory workers in the area, now a shabby shopping mall. Lenin’s statue and the hammer and sickle on the façade of the Soviet building have not been removed to a “Fallen Monuments” park like the one we visited in Moscow, and his statue with the raised arm still shows the way on the square in front of the Finland Station (we had been re-reading Edmund Wilson’s book.) The temporary exhibition of extravagantly lavish costumes worn by the army of palace servants we saw at the Hermitage was another reminder of why the revolution had to happen. Sustaining it through the decades; a world war; centralized power; and a lack of understanding about the transformation of a proletarian consciousness was quite another matter.

SUSANA AND GEOFF’S TRIP TO MOSCOW AND SAINT PETERSBURG, JULY-AUGUST 2014

SHHHHHHH!!! The young guards were, very loudly, making sure we didn’t make any noise going down the steps of Lenin’s Mausoleum in almost complete darkness. It’s impossible to tell if the figure lying in state with face and hands precisely lit is the real mummy, or a wax representation. All the same, we wanted to say goodbye in our last day in Moscow to the symbol of the momentous social changes brought about by the October 1917 revolution. Goodbye, Vladimir Ilych. Goodbye, John Reed and Alexei Shchusev buried with many others along the Kremlin wall.

|

| Red Square. From left: GUM, St. Basil's, Lenin's tomb (click for larger view) |

|

| Considering an alternative to the Moscow subway |

Even the Cathedrals within the Kremlin walls followed a similar pattern, churches meant for a privileged few and with no ambition to include the unwashed masses. We were more impressed with the model of Catherine the Great’s insanely ambitious Grand Kremlin Palace, now in the Architecture Museum than with the existing Kremlin itself. Had it been built, monumental Neo-Classical double colonnades would have surmounted the entire Kremlin Wall facing Red Square.

|

| Christ the Savior and Tsereteli sculpture |

Among the dozens of house museums where artists and writers lived, the one I wanted to see most was that of Anatoly Lunacharsky, Lenin’s Commissar of Enlightenment, a great intellectual and promoter of the artistic avant-garde; he staged a happening avant la lettre, a trial against God for crimes against humanity, in which the deity was condemned to death and “executed” by a firing squad shooting machine guns into the sky. When we could gолигарх, i.e., “oligarch”.

et no answer on the phone for an appointment, we simply showed up at the address and rang the bell. A burly man— evidently the caretaker — came down to inform us, by gesture and the few words we could understand, that the apartment was now privately occupied; with a semi-apologetic grin, he explained in one word:

In both Moscow and St. Petersburg we visited art and political history museums. In Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery annex, we were able to see the 50% of George Costakis’ extraordinary art collection that he was obliged to leave behind when he moved to Greece, including Malevich’s Black Square and some of the best pieces of Natalia Goncharova, which establish her role as the inspiring founder of new movements. It was enlightening to see them for the first time in the context of earlier and later works by Russian artists not well known in the West. The focus of the contemporary art world is Moscow’s “Garage”, a would-be museum currently housed in a temporary, unremarkable structure designed by Shigeru Ban, awaiting its permanent location in a Soviet era pavilion being remodeled by Rem Koolhas, in a clear effort to become an international destination. Although we are not entirely up-to-date with Russian contemporary art, we had liked the rambunctious energy of songspiel videos by the art collective Chto Delat? (What is to be done?) http://vimeo.com/12130035 -- but the exhibition at Garage, with work by artists in the periphery of the Russian Federation about the dislocation produced by the end of the Soviet Union, seemed trite and superficial.

Construction in Moscow’s center, especially in its main radial avenue, Tverskaya Ulitsa, seems to have stopped after Stalin built the Seven Sisters skyscrapers in the late 1940s and early 50s. The foundations for an eighth “Sister” bordering Red Square were used after Stalin’s death for the modern, monstrously big Rossiya Hotel (21-storeys, 3,200 rooms, police station, etc.), the biggest in Europe, which was finally demolished in 2006. It has become a contested site, with public pressure to use it for a park instead of a new entertainment center designed by Norman Foster. But a new International Business Center, boasting Europe’s tallest building, is nearly finished on a site beyond the third ring road. We saw its gleaming towers at a distance during our tour of Constructivist buildings – the workers’ clubs, communal housing and other emblematic projects built during the 1920s that embody the revolutionary social change made into architecture during the Bolshevik government’s first years.

We continued our search for places and buildings of that fateful period when we arrived in picture book Neo-Classical “Peter”. Such buildings can be found mostly in Narvskaya Zastava, the center of the workers’ movement during the events of 1917, still a proletarian neighborhood full of factories and streets with names like “Tractor” or “Barricade”. Two impressive relics are the Kirovsky District Soviet building, municipal offices still used for the original purpose, and the former humongous industrial kitchen supplying hot lunches to factory workers in the area, now a shabby shopping mall. Lenin’s statue and the hammer and sickle on the façade of the Soviet building have not been removed to a “Fallen Monuments” park like the one we visited in Moscow, and his statue with the raised arm still shows the way on the square in front of the Finland Station (we had been re-reading Edmund Wilson’s book.) The temporary exhibition of extravagantly lavish costumes worn by the army of palace servants we saw at the Hermitage was another reminder of why the revolution had to happen. Sustaining it through the decades; a world war; centralized power; and a lack of understanding about the transformation of a proletarian consciousness was quite another matter.

|

| Vladimir Ilyich & comrade, in the Park of Fallen Monuments |

2014/09/01

Will Self declares George Orwell the 'Supreme Mediocrity' | Books | theguardian.com

I surprised myself by agreeing with him! "Wigan Pier", "Down and Out in Paris and London" are important reportage, also "Homage to Catalonia" if you account for the very obvious bias, and even (the much weaker) "Keep the Aspidistra Flying" may be worth reading for the satire (not the characterization or plot drama, which are almost nil), but Orwell as didactic preacher ("Animal Farm", "1984", "Politics and the English Language") really is just mediocre at best. Good reporter, shallow thinker. And barely acceptable as a novelist.

Will Self declares George Orwell the 'Supreme Mediocrity' | Books | theguardian.com

Now I suppose I'd better read something by Will Self.

Will Self declares George Orwell the 'Supreme Mediocrity' | Books | theguardian.com

Now I suppose I'd better read something by Will Self.

2014/08/31

Postscript: Russia and Ukraine

The "pregnancy" metaphor, may be overworked, but this analysis is in line with our impressions from the Russian newscasts and our conversations during our recent visit to Russia:

Russia Is Pregnant with Ukraine

New York Review of Books, 2014.07.24

2014/08/19

Revolutionary thought, from Michelet to Lenin

TO THE FINLAND STATION: A Study in the Writing and Acting of History by Edmund Wilson

TO THE FINLAND STATION: A Study in the Writing and Acting of History by Edmund WilsonMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Yesterday I devoted a pair of hours to a review of Edmund Wilson’s To the Finland Station, composing directly on the Goodreads review screen as was my habit. But when I was finally satisfied with it and pressed the button to “Publish,” the review vanished! Replaced by the sign-in screen for Goodreads. I won’t do that again. From now on, I’ll compose my reviews in Word, then post them — so if the link fails, I’ll still have my draft.

I won’t try to reconstruct my review.

Instead, I refer you to the very good, thorough critique of this book by Louis

Menand, in The New Yorker, March 24, 2003, The

Historical Romance: Edmund Wilson’s adventure with Communism.

Menand will tell you how Wilson got the

idea for the book and his many problems in writing it, including his changing

attitudes toward the Soviet Union. Wilson, beginning this huge project in the

1930s, had got himself committed to an overly rosy picture of the Soviet Union,

one that no longer convinced even him by the time he published the book in

1940. In his new introduction written in 1971 (a year before his death), Wilson

tries to correct that rosy view, at least partially, quoting some very negative

reminiscences by contemporaries of Lenin and making very explicit his disgust

with Josef Stalin, who was barely mentioned in the original book.

More important for contemporary readers, as Menand points

out, is the success of this wide-ranging history of revolutionary thought in

bringing together the ideas and the often tangled lives of those who developed

them, from Jules Michelet to Vladimir Lenin. Wilson here is clearly emulating

Michelet, whose histories of the French revolution he admires for making the past

seem suspenseful and contemporary, viewing events (as much as possible) through

the eyes of the people who were living them.

But the book is really historical

journalism rather than philosophy, where Wilson was hopelessly incompetent —

evident in his chapter on Marx and Engels’ concept of the dialectic. Menand

writes,

“The dialectic was just the sort

of high-theory concept that Wilson reflexively avoided. At the same time, he

was not a man quick to concede his ignorance, and he devoted a chapter of his

book to explaining that the dialectic is basically a religious myth (a

characteristic exercise in journalistic debunking). Wilson had no idea what he

was talking about. ”

Menand however does, and explains it in as

good a two-paragraph exposition as you’re likely to find of this subtle and

complex way of thinking. I recommend it. Here is Menand's summary:

The two-paragraph explanation [Wilson] gives of the term at the beginning of the chapter on “The Myth of the Dialectic”—the thesis-antithesis-synthesis model—is not the dialectic of Hegel. It is the dialectic of Fichte. And Marx and Engels did not name their method “dialectical materialism.” That was a term assigned to it by Georgi Plekhanov, the man who, after Marx’s death, introduced Marxism to Russia. Engels referred to the method as historical materialism.

Still, Hegel’s dialectic was part of Marx’s way of doing philosophy, and the use of the dialectic as a historical method is the strongest element in Marxist theory. In the broadest terms, it is a way of treating each aspect of a historical moment—its art, its industry, its politics—as being implicated in the whole, and of understanding that every dominant idea depends on, defines itself against, whatever it suppresses or excludes. Dialectical thinking is a brake on the tendency to assume that things will continue to be the way they are, only more so, because it reminds us that every paradigm contains the seed of its own undoing, the limit-case that, as it is approached, begins to unravel the whole construct. You don’t have to be an enemy of bourgeois capitalism, or believe in an iron law of history, to think this way. It’s just a fruitful method for historical criticism.

View all my reviews

2014/08/13

Historical fiction

Here, in this essay by Sam Jordison, is a clear defense of a genre that needs no defense — historical fiction has always been with us, since Homer, and continues to have very wide readership. Even though some of it is no more that what Hilary Mantel described as "chick-lit with wimples."

What interested me most was this other quote from Hilary Mantel, on the special challenge for serious exploration of the past:

Historical fiction can speak very clearly to the present and the past | Books | theguardian.com

What interested me most was this other quote from Hilary Mantel, on the special challenge for serious exploration of the past:

"The grumbling is aimed at literary fiction set in the past,In the Paris Commune, the most transgressive "obscenity" is not sexual, but the subversiveness of the exalted revolutionary ideals. And the terrible bloodiness of the affair, especially in that final week of May 1871, and the disturbing parallels to cruel events today. This all may surpass the borders of what readers can accept. I shall try to take my readers into that disturbing, exhilarating world, though I know many may be reluctant to go there.

which is accused of being, by its nature, escapist. It's as if the past

is some feathered sanctuary, a nest muffled from contention and the

noise of debate, its events suffused by a pink, romantic glow. But this

is not how, in practice, modern novelists see their subject matter. If

anything, the opposite is true. A relation of past events brings you up

against events and mentalities that, should you choose to describe them,

would bring you to the borders of what your readers could bear. The

danger you have to negotiate is not the dimpled coyness of the past – it

is its obscenity."

|

| Paris sous le drapeau rouge. Place de l'Hôtel de Ville. De Vieux papiers (blog) |

Historical fiction can speak very clearly to the present and the past | Books | theguardian.com

2014/08/06

Russians today

Back home in Spain after two weeks in Russia and reflecting on what it all has meant. Our last visit in Saint Petersburg (Monday, 2 days ago), after the ornate Italianate-Slavonic Smolny cathedral and monastery, was to the decidedly un-ornate and still busy Finland Station, Finlyandskaya Vokzal, a plain white railroad and Metro terminal behind a magnificent statue of Lenin pointing to the future. And yesterday on the plane, I finished Edmund Wilson's look back to the history culminating in that gesture. I'll have more to say about that ambitious, stimulating and antiquated book, To the Finland Station, in a future essay. For now, just some general impressions of Russia.

First and most importantly, the people. Everyone we met, anyone we approached to ask directions or anything else, was friendly and helpful — surprisingly so, at first, until we realized that that was the norm. Our initial surprise was because of the difference in facial expression and body language. Russians look severe until you give them a reason to look at you with interest and to smile, which requires no more than that you take an interest in them by saying "Hello" or "Excuse me, do you know…?" And the typical Russian stride takes command of the ground more definitively than the lighter, quicker steps we're used to. Russians appear brusque and direct to Westerners (just read the guide books), which I quite liked. When they try to help you, they get right to the point, and may go so far as to walk out of their way to point and show you what it is they think you asked. At least, that was our experience. It's a huge country with millions of individuals and regional contrasts, but such were the people we encountered in Moscow and St. Petersburg. A second general impression was the over-all cleanliness of streets and sidewalks, and —mostly — the good repair of public spaces, as compared to, say, Madrid or New York. No obvious garbage strewn on the streets or rivers. Nor did we see much obvious poverty, even outside the central tourist areas, except for a few, mostly elderly women, mendicants. Nor any jostling or shoving — beyond unavoidable pressing together —even on the crowded subway cars.

Finally, as I've already noted in this blog, there appears to be an attitude of critical respect toward the whole, still recent Soviet experience. Most of the statues and images of Stalin have disappeared (except as jokey designs on matryoshki and other souvenirs), but many of Lenin remain, and at least some of the impressive architecture is being restored.

Unfortunately I don't have the language skills for more than minimal observation, so I can't tell you much about public opinion. From comments by our Moscow guide, and the flags and collection booths for money for the people of Donbass, it was evident that a sizable part of the population think that Russia must support the separatists in eastern Ukraine, and from all that and what we read or saw in Russian media, that US accusations against the Russian government are baseless and motivated by competitive interest. And people seem very satisfied to have recovered Crimea.

.JPG) |

| Finland Station, St. Petersburg |

Finally, as I've already noted in this blog, there appears to be an attitude of critical respect toward the whole, still recent Soviet experience. Most of the statues and images of Stalin have disappeared (except as jokey designs on matryoshki and other souvenirs), but many of Lenin remain, and at least some of the impressive architecture is being restored.

Unfortunately I don't have the language skills for more than minimal observation, so I can't tell you much about public opinion. From comments by our Moscow guide, and the flags and collection booths for money for the people of Donbass, it was evident that a sizable part of the population think that Russia must support the separatists in eastern Ukraine, and from all that and what we read or saw in Russian media, that US accusations against the Russian government are baseless and motivated by competitive interest. And people seem very satisfied to have recovered Crimea.

2014/08/04

Do svidanya, Rossiya

Or to say this in proper Russian, До свида́ния, Россия. This is our last night in St. Petersburg and in Russia. We're a bit tired, so I'll just mention some highlights since my last blog entry.

The Russian Museum — Best collection we've seen of not only constructivist art (Malevich, Popova, Tatlin and others), but also of their contemporaries working from different premises in that brief golden age of post-October Revolution creativity.

Museum of Political History — The two houses (one of a ballerina favored by Nicholas II, the other of a rich merchant) that became Lenin's headquarters in Petrograd, now joined as this museum, are themselves well worth seeing. The exhibits are a detailed history of Russia and the USSR, and now simply "Russia" again, 1917 to the present. In Russian, but with booklets with English-language explanations. Lenin's Petrograd office was in the best corner of the merchant's house.

Constructivist architecture in a working-class district of the city, far off the tourist route, but we got to see the most important examples still standing. Details to come.

2014/08/03

Russia, revolution and me

On the 4 1/2 hour train ride from Leningradsky Station in Moscow to Moskovskaya Station in Saint Petersburg last Thursday, I continued re-reading Edmund Wilson, To the Finland Station.

I've now got close to the end of this history of revolutionary thought from Michelet to the 1917 revolution, and the arrival of Lenin and other exiles at the Finland Station in Petrograd (as the city was then known), which we plan to see tomorrow. Meanwhile, while visiting museums (the Hermitage, Museum of Russian Art) and monuments and churches and walking all over the central city in this great heat, I've been reflecting on what this visit means for me and what I've defined as my life projects.

The most immediate of those projects is completing my novel about the Paris Commune. Wilson is little help there; his too-brief summary is not only mistaken in some details, but treats the whole adventure with detached bemusement. But Wilson and this Russia visit both help me understand better the larger and longer-lasting context of that adventure. More important, they have led me to understand this novel in larger terms. What I really aim to do is understand all of social change, the revolutionary impulse, how it gets mobilized, its splits and contradictions, and especially the conflicts ensuing upon initial victory. The Paris Commune of the spring of 1871 is but one essential chapter. It inspired Lenin and all the other Russian revolutionaries, which is one reason it is essential. The other is that it was a tightly condensed laboratory experience that suggests almost all that can, or has, happened, not only in Russia 1917-1920, but also Mexico 1910 and after, Cuba 1956 (landing of the Granma) and on, and so on. I don't know how much of all this I'll be able to complete before that great, final deadline, but the whole picture, however dimly, will be in my mind as I continue.

So I see these questions as parts of two life projects: 1, to write fiction that helps me and my readers enter these processes emotionally, and 2, to analyze them as the sociologist I was trained to be.

And finally there is a much smaller, less ambitious project: for over 50 years I've wanted to learn Russian, and now I'm doing it. I've begun working through the originals, with the help of the translations, in a bilingual edition of Osip Mandelstam's verse, and loving it. This trip has been the great stimulus.

|

| Lenin's train. From Canadian Military History |

The most immediate of those projects is completing my novel about the Paris Commune. Wilson is little help there; his too-brief summary is not only mistaken in some details, but treats the whole adventure with detached bemusement. But Wilson and this Russia visit both help me understand better the larger and longer-lasting context of that adventure. More important, they have led me to understand this novel in larger terms. What I really aim to do is understand all of social change, the revolutionary impulse, how it gets mobilized, its splits and contradictions, and especially the conflicts ensuing upon initial victory. The Paris Commune of the spring of 1871 is but one essential chapter. It inspired Lenin and all the other Russian revolutionaries, which is one reason it is essential. The other is that it was a tightly condensed laboratory experience that suggests almost all that can, or has, happened, not only in Russia 1917-1920, but also Mexico 1910 and after, Cuba 1956 (landing of the Granma) and on, and so on. I don't know how much of all this I'll be able to complete before that great, final deadline, but the whole picture, however dimly, will be in my mind as I continue.

So I see these questions as parts of two life projects: 1, to write fiction that helps me and my readers enter these processes emotionally, and 2, to analyze them as the sociologist I was trained to be.

And finally there is a much smaller, less ambitious project: for over 50 years I've wanted to learn Russian, and now I'm doing it. I've begun working through the originals, with the help of the translations, in a bilingual edition of Osip Mandelstam's verse, and loving it. This trip has been the great stimulus.

2014/07/31

Moscow: dead Lenin

It is a quasi religious experience, after standing in line in the hot July sun and finally passing the security checkpoint, to file past the red granite tombstones of Communist heroes — John Reed among them (no women, as far as I could see, though I didn't actually manage to read all the names) — and then enter the dark descending staircase. Uniformed honor guards signaled vigorously for me to take off my cap and hushed everybody. Then, after another turn in the dark passageway, you file past the waxy figure, dressed as though to chair a meeting or give a speech. The guards keep everybody moving so soon we are back in the bright sun, walking past still more tombstones and plaques with names of dead Communists.

Today's Russians must view Lenin much the way Americans are supposed to think of George Washington, as the founder (or "father") of the modern state, meriting the same kind of respect as Peter the Great, the motor force of an earlier great modernization. Their respective ideologies, like Washington's supposed "deism", are little more than historical curiosities — very few Russians today call themselves "communists". But Lenin's thinking may still offer us some good guidelines, both regarding political strategy (his ideas about how to gain and extend power were most effective) and

larger economic questions (imperialism, for example). He may not have been a pleasant man to deal with (I'm remembering Struve's and Valentinov's memoirs, quoted by Edmund Wilson in his 1972 introduction to To the Finland Station). But he was a brilliant and audacious one. And Russia could not have become the power it is today without the consolidation of the centralized, modernizing state, difficult to imagine under the Mensheviks or any of the other contenders of 1917-1920.

Olga Boiko has posted historical photos of the mausoleum, together with interesting commentary

Olga Boiko has posted historical photos of the mausoleum, together with interesting commentary

2014/07/30

Moscow: history and literature

After browsing around the monastery of St. Peter on the Hill (more divinity-powered icons), we paid hommage to a more recent summoner of magical forces, Mikhail Bulgakov, by a visit to Patriarchs Ponds, the opening scene of Master and Margarita, which Susana has been reading. From her descriptions (I haven't got into it yet), its miracles and black magic are even weirder than the stuff in the churches.

From there it was only a short walk to the Museum of Contemporary History (an oxymoron in its English translation — what the Russians mean by современной истории is "recent" history, since Alexander II - 1856-1881 — to today). Fascinating collection of objects and images, including film footage of battle scenes and troops in World War I, political rallies and fighting in 1905 and 1917 and following. All the explanatory labels were in Russian and we had only an hour before closing time, so I had hardly time to consult my dictionary for some of the more curious exhibit cases, but we didn't really need to to get the gist of a history we've long studied from other sources. It could all have been made much clearer with a better arrangement, and more information in other languages — Japanese tourists, for example, would surely be interested in the section on the Russo-Japanese war, a military and financial disaster for the Russian Empire that largely provoked the 1905 revolution. Still, the exhibits as a whole helped us imagine those lives and that history more vividly.

Then a longer walk to the twin bookstores at 18 Kuznetsky Most, where I was hoping to find a bilingual edition of some classical or contemporary Russian literature. But no. One store had only Russian, the other only foreign languge (mostly English), no bilingual editions in either. And no store clerk in either store who really understood English, so I was forced to exercise my pitifully minimal Russian. I remembered a book that had made a powerful impression when I'd read it in translation and decided to find the Russian text: Isaac Babel's "Red Cavalry". And I made myself understood— I bought a 1986 paperback collection that includes not only the 34 very short stories in Конармия but also his Одесские рассказы (Odessa stories). And to create my own bilingual experience, I searched on-line for a translation in some language I can read, and was delighted to discover on Kindle a 1928 translation into French on which Babel himself (who spoke and wrote French fluently) had collaborated. The translator seems to have known Babel well, and his introduction is a delight. More on that later — potom, as the Russians say.

Meanwhile, on another much in the news and people's concerns:

US-Supported "Good Guys" Firing Ballistic Missiles in Ukraine?

From there it was only a short walk to the Museum of Contemporary History (an oxymoron in its English translation — what the Russians mean by современной истории is "recent" history, since Alexander II - 1856-1881 — to today). Fascinating collection of objects and images, including film footage of battle scenes and troops in World War I, political rallies and fighting in 1905 and 1917 and following. All the explanatory labels were in Russian and we had only an hour before closing time, so I had hardly time to consult my dictionary for some of the more curious exhibit cases, but we didn't really need to to get the gist of a history we've long studied from other sources. It could all have been made much clearer with a better arrangement, and more information in other languages — Japanese tourists, for example, would surely be interested in the section on the Russo-Japanese war, a military and financial disaster for the Russian Empire that largely provoked the 1905 revolution. Still, the exhibits as a whole helped us imagine those lives and that history more vividly.

Then a longer walk to the twin bookstores at 18 Kuznetsky Most, where I was hoping to find a bilingual edition of some classical or contemporary Russian literature. But no. One store had only Russian, the other only foreign languge (mostly English), no bilingual editions in either. And no store clerk in either store who really understood English, so I was forced to exercise my pitifully minimal Russian. I remembered a book that had made a powerful impression when I'd read it in translation and decided to find the Russian text: Isaac Babel's "Red Cavalry". And I made myself understood— I bought a 1986 paperback collection that includes not only the 34 very short stories in Конармия but also his Одесские рассказы (Odessa stories). And to create my own bilingual experience, I searched on-line for a translation in some language I can read, and was delighted to discover on Kindle a 1928 translation into French on which Babel himself (who spoke and wrote French fluently) had collaborated. The translator seems to have known Babel well, and his introduction is a delight. More on that later — potom, as the Russians say.

Meanwhile, on another much in the news and people's concerns:

US-Supported "Good Guys" Firing Ballistic Missiles in Ukraine?

2014/07/29

Moscow: seeing what's left of constructivist architecture

|

| Rusakov Workers Club by Melnikov |

As with the constructivist art that I mentioned yesterday (and which in some cases was produced by the same people who designed the most impressive architecture), that creative, open and experimental period did not last. The art was mostly destroyed or hidden with the bureaucratization of the Soviet state and the imposition of "correct" tastes. The architecture was neglected or altered, sometimes drastically, for uses for which it was never intended. But some of it is still standing, and some has even been conscientiously restored.

It would have been impossible for us to get to so many widely separated sites on our own in one day, or for us to negotiate in Russian with the doorkeepers so we could see the interiors of some of these places. Fortunately, we had hired Arthur Lookyanov to get us to all these places, and Arthur is a very persistent and organized guide — with very good English, an air-conditioned car with GPS, and photographic skill and equipment. Susana had sent him in advance the list of sites, and he had worked out the most efficient itinerary; he was very dogged in trying to get us into places, some of which were in reconstruction or were in top security sectors — a power plant, for example, or the famous Shukov radio tower.

He took much better pictures than we would have managed. I'll share them with you once he sends them. If you're planning a tour of Moscow, he would be a good guide: Moscow Driver is his website.

2014/07/28

Fallen Monuments

|

| "USSR - Bulwark of Peace" - photo Folkestone Jack

This for me is the most impressive piece in the Park of the Fallen Monuments, because it is not merely the image of a man that has fallen but a once noble and inspiring ideal.

Park of the Fallen Monuments

Acccording to the Guía Roja de Moscú, "This shield was in the southeastern sector of Moscow, at the intersection of Avenue Lenin and Kravchenko Street, placed there in the 1970s, the work in aluminum of S. Shchekotikhin. The shield and slogan were dismanteled at the beginning of the 90s and ended up in the Muzeon" (of Fallen Monuments) next to the new Tryetyakov Galereya. |

2014/07/27

Moscow, days 3-4: Partizani, Putin-mania & konstruktivizma

Yesterday, we joined the crowd at the flea-market "vernissage" in Ismailovskaya park, near the Partizanskaya Metro station. Like the station, the flea market was full of "Great Patriotic War" memorabilia, and much more : matryoshka dolls, bad art, Soviet-era books, maps and documents,ancient post cards, goofy sculptures, and even some surprisingly clever handicrafts. Vladimir Poprotzkin, for example, offers matryoshkas of works by famous artists; Susana bought his Malevich doll, one tiny reproduction nested in another nested in another of the famous suprematist paintings. We were also impressed by the detailed lighthouse models by Andrei Savarov.

And then there were all the Putin images in coffee mugs: posing shirtless and flexing, or grimacing or snarling while saying things like "Crimea is ours!" And Russia's English-language TV station that night was equally belligerent, denouncing what they said (in perfect American accents) were absurd US propaganda slurs implying that Russia had something to do with the downing of the Malaysian jet liner while minimizing Ukrainian government terrorism. We weren't convinced by this view, but apparently many Russians are.

At Crash Scene of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, Rebels Blame Ukraine

None of this tension has been observable on the streets of Moscow this weekend, where Gorky Park and the whole south bank of the Moskva river was in festival mood. And this in great heat, well over 30º. Most memorable today: the Costakis collection of Russian avant-garde art, or at least part of it, in the Tretryakov Gallery annex (fortunately air-conditioned). The story of how this very perceptive collector managed to save so many marvelous works — besides Malevich, pieces by Tatlin, Rodchenko, Popova and many others — from oblivion and almost certain destruction is told in a film.

More later. It's been a fatiguing day.

And then there were all the Putin images in coffee mugs: posing shirtless and flexing, or grimacing or snarling while saying things like "Crimea is ours!" And Russia's English-language TV station that night was equally belligerent, denouncing what they said (in perfect American accents) were absurd US propaganda slurs implying that Russia had something to do with the downing of the Malaysian jet liner while minimizing Ukrainian government terrorism. We weren't convinced by this view, but apparently many Russians are.

At Crash Scene of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, Rebels Blame Ukraine

None of this tension has been observable on the streets of Moscow this weekend, where Gorky Park and the whole south bank of the Moskva river was in festival mood. And this in great heat, well over 30º. Most memorable today: the Costakis collection of Russian avant-garde art, or at least part of it, in the Tretryakov Gallery annex (fortunately air-conditioned). The story of how this very perceptive collector managed to save so many marvelous works — besides Malevich, pieces by Tatlin, Rodchenko, Popova and many others — from oblivion and almost certain destruction is told in a film.

More later. It's been a fatiguing day.

2014/07/26

Moscow: day 2

On Friday we toured the churches and gardens inside the red walls of the Kremlin, full of tombs and images of saints and tsars, and then took a great leap into another time and mind set with the exhibition in the State Historical Museum, "The myth of the beloved leader." For this small but densely packed show, the curators brought out of hiding objects, posters, videos and other images related to the creation and elaboration of the myth that was supposed to substitute for the suppressed myth represented by those churches: the enlightened heroism and steadfastness of Lenin, and the continuation of his spirit in Iosif Vissarionovich Stalin ( Russian : Иосиф Виссарионович Сталин).

Stalin's version of the myth required distorting or obliterating much of the turbulent story of the creation of the Soviet Union and of the Comintern, which is why so much of the material in this exhibition had been hidden after Stalin consolidated his power in 1927. Many of the heroes of those earlier phases had been declared enemies by Iosif Vissarionovich — Trotsky being the best known, but there were scores of others who had worked closely with Lenin but now were to be expunged from the record and, when possible, killed. But all those bright, enthusiastic faces have been brought back to view, in photos, documents and the vivid sketches by Isaak Brodsky and, most impressively, in his huge painting (1920-1924) of the Second Congress of the Communist International.

In the full-size original, with the help of an electronic screen provided by the museum, you can pick out Lenin (presiding), Stalin (far to the right of the picture, a few rows in front of the column), Trotsky (behind and to the left of Lenin, leaning over a rail and talking to another comrade), Karl Radek (a special hero of mine— I think he's the man sitting in the same row as Lenin, to his left), Zinoviev, Kamenev, John Reed (the only American I found), plus scores of men and women delegates from Germany, France, Hungary, Bulgaria...

If those early Bolsheviks had only tried to demythologize Christianity as intelligently and respectfully as the museum curators seek to reveal the construction of Stalin's myth of his own continuation of a heroic Lenin, maybe we would not see today so many frightened people pleading for salvation by the saints. But it seems that most people need powerful imaginary companions to get through all our troubles, and for decades, a mythified Stalin-Lenin duo did the job for millions of Russians and others. Now they're gone, and the saints have come marching back.

2014/07/24

Moscow: day 1

We've taken our first day in Moscow slowly, to orient ourselves. Besides getting acquainted with the subways and strolling the length of Varvarka Street (Moscow's oldest), we spent most of the day on and around Red Square, where we plan to return tomorrow for an exhibition that was closed today: "The Myth of the Beloved Leader" at the State Historical Museum. Today we visited the Cathedral of St. Basil the Blessed (a complex of ten churches under as many domes, where we stopped to hear a 4-man vocal group who made a chapel and its labyrinthine corridors vibrate to old Russian paeans to God), GUM and the other part of the historical museum (open today) for pre-20th century Russia.

Vast and overwhelming. So much history, so complex, and all the labels in Russian — which may be why we were the only foreigners we saw in the place. Fortunately Susana had found on the Internet and printed out case-by-case descriptions of things in all the 18th and 19th century halls, but when we got into earlier times — Mongol invasions, medieval salt production (I think that's what a big wooden machine was doing), cruel and primitive weapons, all the way back to the mammoths and giant rhinoceros that were there before the humans — we could call upon only our memories of past readings and my searches through my Russian-English dictionary to interpret what we saw.

Still, it was worthwhile. Viewing clothing, tools, housing and artifacts linked with images we had retained from Tolstoi and every other Russian author who had passed through our consciousness, each of these experiences (reading and seeing) strengthening the other. So we are beginning to feel Russia, which is important to understand it.

And that of course is the main reason I've been studying the language. I've made small but significant progress: people understand me when I ask directions. The next big step will be to understand their answers, but so far, Russians on the street or the subway platform have been very helpful and very patient, and we've been able to find our way.

Vast and overwhelming. So much history, so complex, and all the labels in Russian — which may be why we were the only foreigners we saw in the place. Fortunately Susana had found on the Internet and printed out case-by-case descriptions of things in all the 18th and 19th century halls, but when we got into earlier times — Mongol invasions, medieval salt production (I think that's what a big wooden machine was doing), cruel and primitive weapons, all the way back to the mammoths and giant rhinoceros that were there before the humans — we could call upon only our memories of past readings and my searches through my Russian-English dictionary to interpret what we saw.

Still, it was worthwhile. Viewing clothing, tools, housing and artifacts linked with images we had retained from Tolstoi and every other Russian author who had passed through our consciousness, each of these experiences (reading and seeing) strengthening the other. So we are beginning to feel Russia, which is important to understand it.

And that of course is the main reason I've been studying the language. I've made small but significant progress: people understand me when I ask directions. The next big step will be to understand their answers, but so far, Russians on the street or the subway platform have been very helpful and very patient, and we've been able to find our way.

2014/07/15

Polyglots

Now that I have "re-activated" my long-languishing store of Russian, I got to wondering

How Many Languages Is It Possible to Learn? And this is one of many similar responses I got from Google, this one from The Linguist Blogger.

It appears that the only limit is the time it takes to learn each one. There's no limit to the number we can attain, and there are people who can speak 200 or more — the problem will be to retain them. The human brain has far greater capacity than any of us can ever exploit; it simply forms new neural pathways for every new routine we learn, whether a piece of music, computer code, dozens of PINs, or city map. Or a language. Wow. I'm impressed by my own brain (and by yours, too, and every human's). The amount of lore that a London taxi driver or a Mumbai dabbawalla can keep track of seems astounding — but they are just ordinary people like us, and if we went about it the way they do, we could learn all that too.

But how many languages can one usefully learn? If comparative linguistics is your thing, then maybe learning 200 will be important. For most of us, the answer is only as many as we need, and only as much as we need for our uses— whether as souvenir hawkers in a tourist center, nomads, foreign correspondents, diplomats, international bankers, or casual travelers, et alii. And, use it or lose it; if we cease using a language, we cease reinforcing or creating new neural pathways that let us find the word or phrase we need when we need it. But my experience confirms something in that blog post cited above: once learned, a disused language may not be totally lost.

For now, I'm hoping to be able to ask and understand directions, order food, etc., in Moscow and St. Petersburgh. And maybe even to have a conversation. Learning anything new is a thrill, and languages come more easily to me than, say, computer code or streetmaps or almost anything else. Language is a way into another person's way of thinking, and that's something we all need.

How Many Languages Is It Possible to Learn? And this is one of many similar responses I got from Google, this one from The Linguist Blogger.

It appears that the only limit is the time it takes to learn each one. There's no limit to the number we can attain, and there are people who can speak 200 or more — the problem will be to retain them. The human brain has far greater capacity than any of us can ever exploit; it simply forms new neural pathways for every new routine we learn, whether a piece of music, computer code, dozens of PINs, or city map. Or a language. Wow. I'm impressed by my own brain (and by yours, too, and every human's). The amount of lore that a London taxi driver or a Mumbai dabbawalla can keep track of seems astounding — but they are just ordinary people like us, and if we went about it the way they do, we could learn all that too.

But how many languages can one usefully learn? If comparative linguistics is your thing, then maybe learning 200 will be important. For most of us, the answer is only as many as we need, and only as much as we need for our uses— whether as souvenir hawkers in a tourist center, nomads, foreign correspondents, diplomats, international bankers, or casual travelers, et alii. And, use it or lose it; if we cease using a language, we cease reinforcing or creating new neural pathways that let us find the word or phrase we need when we need it. But my experience confirms something in that blog post cited above: once learned, a disused language may not be totally lost.

For now, I'm hoping to be able to ask and understand directions, order food, etc., in Moscow and St. Petersburgh. And maybe even to have a conversation. Learning anything new is a thrill, and languages come more easily to me than, say, computer code or streetmaps or almost anything else. Language is a way into another person's way of thinking, and that's something we all need.

2014/07/14

Too many ambitions

|

| Banner of Spain adopted in 1981 |

|

| Banner of the II Republic, 1931-39 |

BUT that will be a bigger job than I can take on right now. I've been trying to do too many things at once: write a novel about the Paris Commune, participate (even if marginally) in political movements in Spain, comprehend 21st century capitalism (Piketty), and now a trip to Russia. All I can say is, keep an eye on events here, and I'll try to give you a coherent account when I get back.

Right now I'm working as fast as I can to learn Russian well enough to get around in Moscow and St. Petersburgh. This is a new task I've assigned myself, but it's something I've wanted to do for many years, since I first took a Russian language course in college but was too undisciplined (it was my freshman year) to really learn it.

It may not look like it, but (for me) all these projects are parts of one bigger one: understanding the past attempts to change the world (Hobsbawm) in order to guide us to do it better.

That's why I am researching the Commune, to be able to tell part of its story in a novel, as it might have been experienced by a young revolutionary worker.

That's why I am researching the Commune, to be able to tell part of its story in a novel, as it might have been experienced by a young revolutionary worker.| Flag of the Soviet Union, 1923-1991 |

| |

| Russian Federation, since 1993 (white band on top) |

(By the way, if you too are trying to learn Russian, I've had good experience with this on-line course: Russian Accelerator.)

2014/07/10

What we talk about when we talk about the Left

Left In Europe by David Caute

Left In Europe by David CauteMy rating: 3 of 5 stars

Reflecting on the confusion of aims and strategies of all the parties and movements calling themselves "Left" in Europe today, I turned again to this little book with its capsule histories and profuse illustrations (engravings, photos, posters) of revolutionary movements from the French Revolution of 1789 to the mid-1960s. Caute's intention was evidently to rescue the notion of the Left from many misunderstanding and confusions, but he does not manage to come up with a concise, convincing definition of his own. He critiques descriptions such as anti-racism, anti-clericalism, pacifism, and social reformism because conservatives and even reactionaries may adopt similar positions (Bismarck and Napoleon III were reformists, etc.). Nor are the movements he considers Left always anti-authoritarian (remember Lenin's vanguard party) or democratic, in the sense of always accepting what the greater number of voices demand; he suggests that "'popular sovereignty' is preferable to 'democracy' as a term descriptive of the central creed of the Left" [p. 32], but that hardly solves the problem.

I don't think there's any point in trying to define the Left, with clear delineations of what it includes or excludes; no definition — whether by Lenin, or Caute, or Hugo Chávez or anybody — will be accepted by everybody. The term originated from a vote in the assemblée nationale in Paris on September 11, 1789, where those opposed to a monarchical veto took seats to the left of the chairman; but those députés did not necessarily agree on anything else. Protest movements, then and now, are volatile and contradictory. What we can do, and what Caute's little book does in part, is describe some of them to find common characteristics and aspirations.

Over 50 years ago I was part of an informal seminar with the very young David Caute (I was 5 years younger), discussing some of these same ideas. The controversies live on.

View all my reviews

2014/06/18

Spain: Populists, demagogues and democrats

"Populism" has become the big scare word in political invective of Spain, especially since the débâcle of the big established parties in the European Parliament elections. What politicians and supporters of those parties mean is any new movement that gathers the votes they think should have gone to them, whether far Right like Marine Le Pen's Front national or socialist like Podemos. What they are implying is something like the movement of the guy grinning in the photo. He called his movement "Fascismo".